Outcomes First Group named one of top super large employers in national Great Place to Work Awards.

Acorn Education proudly forms part of the Outcomes First Group Family, and today it has been announced

I have been fortunate to have worked for the past 12 years as the clinical psychologist at one of the largest schools in the UK specialising in supporting pupils across the age and ability range with a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). It’s great to have the opportunity to write a blog for Autism Awareness Week to share with parents, carers, colleagues, professionals and anyone who would benefit from the information.

What is Autism Spectrum Disorder?

Autism is a relatively common condition, with a current prevalence of 1-2% in the general UK population, such that around 700,000 people have a diagnosis of ASD in the UK. Findings in the USA indicated 1 in 54 children being diagnosed with the condition. Current large scale research studies found that about 80% of the risk of developing ASD was from genetic factors, with the remainder of the risk to as-yet-unidentified environmental causes. The most up to date estimate of the ratio of boys to girls is 3:1, however, it is not clear whether girls present differently and are therefore at risk of missing out on support. Findings also highlight persistent racial/ethnic disparities, with those described as having a ‘white’ ethnicity more likely to be given the diagnosis than those from other ethnic backgrounds. There is no biological reason for this so this obviously raises concerns that some children are being missed, and for a range of possible reasons.

ASD is present from birth and impacts in the following ways:

Like everyone, people with autism have things they are good at as well as things they struggle with. The challenges described above mean that an autistic person is likely to need extra help in these areas in order to have access to, enjoy, and live a full life. ASD occurs across the ability range from having a learning disability to high intelligence. It is considered to reflect a neurodiverse way of thinking about and viewing the world and as such, people with autism can bring a whole range of valued skills and talents – scientific, technical, creative and social – to the workplace and beyond. ASD can co-occur with other neurodevelopmental conditions, such as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Dyslexia, and sometimes with epilepsy. Autism is viewed as a spectrum due to both the way it impacts each person differently and the degree. So, for example, young autistic people may experience sensory challenges (e.g. noise, heat) in different ways, and this may also be moderated by their perception about the level of control they have over their environment: our packed Christmas school disco enjoyed by the many pupils who choose to attend and get into the groove is testament to that!

Diagnosing ASD and why a diagnosis helps:

Although ASD is related to genetics, with several genes thought to be involved, it cannot be diagnosed by genetic testing. Instead, a team of professionals – often a paediatrician, clinical psychologist and Speech and Language therapist (SALT) – use specific diagnostic measures that assess behaviour, as well as taking an early developmental history. The team may ask about any problems the child and family are having, watch how the child interacts with other people, and speak to others who know the family and child well, such as GP or school/nursery teachers.

A reliable diagnosis can usually be made by the age of two to three years although sometimes more time is needed first for children who have not had enough opportunity to interact socially with peers. Whilst difficulties regulating emotions, leading to upset behaviour or appearing anxious and avoidant, is now considered ubiquitous to ASD, these behaviours can be mistaken for a child being deliberately ‘naughty’ or ‘shy’. Additionally, some behaviours that indicate ASD can be quite subtle such as using quite sophisticated social interaction but only for the purposes of achieving the aim of following a preferred agenda (i.e. not for reciprocal reasons) so some people do not get diagnosed at all or do so when they are in their teens or adulthood.

Having a diagnosis can help in several ways, including:

What to do if you think a child is showing signs of autism:

It is important to share any concerns as soon as possible with the GP, SENCO, Health visitor or therapy professionals, so that a referral for an assessment can be made. Once a diagnosis is given this enables intervention and support to begin as soon as possible.

Signs that may indicate a young child would benefit from an assessment include:

Signs of autism in older children include:

If you suspect a child is showing signs of needing an assessment it can be helpful to write a list of the signs of autism and ask others who know the child well if they have noticed any possible signs you could include, and to bring this information to the assessment.

What helps:

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) published evidence-based best practice guidance to help support autistic children and young people called: “Autism spectrum disorder in under 19s: support and management” (NICE 2013). The recommendations emphasise focusing input into the areas that appear most impacted by the core difficulties in ASD (as described above) using interventions that help the young autistic person, their families, and teachers/carers from the early years through transition into young adult life.

NICE recommends using a range of psychosocial interventions to help build up social communication skills and positive relationships, and using Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) interventions to support helping the young autistic person to increase their skills in emotion recognition training and safe, functional emotion regulation. All interventions need to be adapted by using visual, structured, gradual/graded (low arousal) approaches that preferably fit with the autistic person’s interests as this helps engage the person best and helps the intervention make most sense to them. Most importantly, all approaches need to be joined up, such that all those around the young person are working together within the same framework and sharing goals. Examples of interventions are: Social Stories; Attention Autism, Play-based interaction, Intensive Interaction, SPELL and TEACCH.

An example of an intervention:

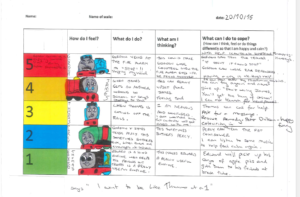

As an example, to support a young autistic person learn helpful skills in situations that are leading to upset and avoidance, we could start by building a relationship by taking an interest in their preferred activities. This is creating a calm (low arousal) environment for learning. For example, for an autistic child who is interested in Thomas the Tank Engine, we could create a structured session where we each have time to talk about the different engines, in doing so, appreciating the child’s interests, working collaboratively and modelling the social skill of reciprocal conversation. We could then introduce a visual showing a structured presentation of different emotions – such as the ‘Incredible 5 point Scale’ or ‘Zones of Regulation’ – and use the events in the Thomas stories to link with the various emotions on the visual, noting how the engines asked for help when feeling ‘up at a 3 on the 1-5 scale’ with a task they found difficult. We can then broaden this to thinking about the various emotions the young person has in their own day, to increase their emotion literacy. These can then be put onto their own visual.

In getting to know the young person we can begin to empathise and validate their emotions as well as provide explanations about how the social world works – for example, we can empathise that they feel anxious and annoyed when they have a new work task, as well as clarifying that having a go at something new is a very useful life skill. We can show how it helped Thomas the Tank engine and find some examples from the child’s life too. Moving forwards, we can look at skills the person already has when anxious or annoyed, ‘up at a 3’, such as taking a break, and support them to gradually extend that skill towards sharing how they feel, requesting a break, then returning to the task and accepting help to have a go at it. These further skills could then be put onto the visual over time. Positive feedback would be important at all times, as well as all those working with the child engaged in a joined-up way, such as having the visual in class.

Finally – and most importantly:

I wanted to end by sharing reflections from an older pupil who has attended one of the schools in our wider group since his primary school years and is off to college in September. I asked him what he would like to say for Autism Awareness Week. He firstly wanted others to recognise the huge diversity within autism – where different aspects of the condition can impact each person very differently – and that it’s really important people understand that. He described that in his younger years he had experienced a lot of feelings of rage and social awkwardness and this had felt really challenging. He said how it had made him become the young man he was today to have attended a setting that understood these challenges and who helped him to learn the skills to develop into someone who could now manage emotions better and who felt more able to speak up for himself. He also spoke of the great value of his own family being so open to having conversations together to make helpful changes when needed. We agreed how hard he had worked to make this progress and how wonderful it was that he was looking forward to going to college to study subjects he felt passionate about.

By Dr Nicky Greaves, Consultant Clinical Psychologist March 2021